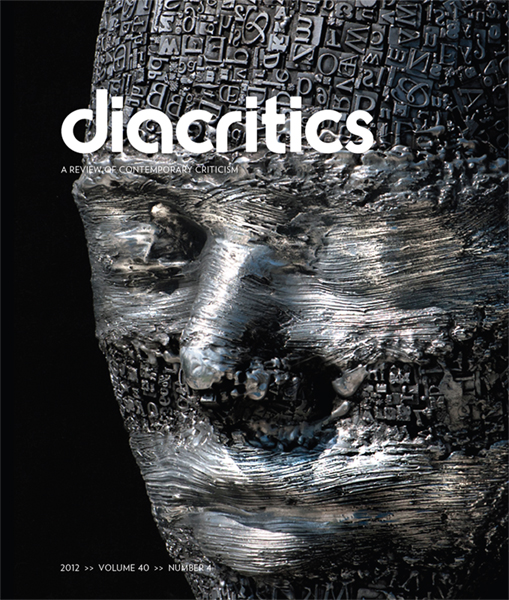

Waiting for the Penny, gilded copper

With the penny headed for obscurity, creative types are finding inventive ways of transforming the humble metal into art.

By: David Graham Living, Published on Fri Feb 01 2013. Life The Star

The penny is dead.

Long live the penny.

As Canada’s smallest currency fades into extinction, artists and crafts people across the country are searching for ways to keep its memory alive — to repurpose the unlucky penny into a lasting treasure.

The Royal Canadian Mint has already ceased production, and the one cent piece will be stricken from circulation on Feb. 4, “due to its excessive and rising cost of production relative to face value,” according to its website.

There were other reasons to stop producing and circulating the penny. Canadians had been hoarding them for years — in glass jam jars and plastic ice cream containers. Their diminished value made them a nuisance to carry around. While at face value a penny costs a penny, in fact the penny costs 1.6 cents to produce, distribute, handle and process.

There were environmental concerns as well. Eliminating the penny means saving base metals — the penny is 94 per cent steel, 1.5 per cent nickel and 4.5 per cent copper plating or copper-pated zinc — and energy.

In the end it came down to dollars and cents. Removing the penny from our daily lives will save taxpayers millions. While pennies can still be used in cash transactions, “with businesses that choose to accept them” they are — for all intents and purposes — on a fast track to oblivion.

For months Canadians have been searching for ways to shed their collections of coppers.

Some have returned them to banks and financial institutions that forward them to the mint to be melted down. Others have donated them to charities. Consumers will be able to redeem their pennies at financial institutions indefinitely. About 35 billion pennies have been minted in Canada since 1908.

But artistic Canadians have been putting the penny to work in new ways. Though Section 11 of the Department of Justice Currency Act prohibits the altering or destruction of Canadian coins, the Minister of Finance has issued a number of licences under this section to artists.

Dale Dunning, a sculptor in Almonte, Ont., has a studio called Lost and Foundry that specializes in repurposing all manner of metals. Dunning, who has created many sculptures in the shape of the human face, took the opportunity recently to design and build a larger-than-life mask made from pennies.

Dunning says he has been using the shape of the human face in his art for more than 10 years — creating his sculptures in a variety of sizes and in a variety of mediums, including bronze and aluminum.

“There are no necks and the egg shape has only the suggestion of eyes, nose and mouth,” he says, explaining that he always makes the faces either larger or smaller than life. “When they are life size, people have a visceral reaction to them. They look like a decapitated head. Once they are larger or smaller they become a metaphor.” The penny sculpture has a slot in the forehead, to evoke piggy banks and saving.

Dunning has been drawn to the concept of repurposing metals for years. One of his most striking faces was created from 20 gallons of lead type that had been removed from a local printing operation.

For his “Waiting for the Penny” project he used several hundred pre-1987 coppers.

“That’s when they started to put zinc in the penny,” he says.

For the face Dunning heated each penny until it was red hot then cooled it quickly, a process called annealing. The change in temperature alters the molecular structure of the penny which makes it malleable, he explains. That allowed him to mould the pennies to the contours of the face — around the nose and into the eyes. He reinforced the fragile silver-soldered sculpture with steel bars and sandblasted the project to give it a consistent surface. Finally, he gilded the piece with 22-karat gold leaf — so thin it’s actually transparent, he says. “I found it amusing to make it look more valuable than it was, taking something you might throw away — and make it precious.”